Can an AI agent navigate Ghidra, the NSA’s open-source reverse engineering suite, well enough to hack an Atari game? Ghidra is powerful but notoriously complex, with a steep learning curve. Instead of spending weeks learning its interface, what if I could simply describe my goal and let an AI handle the complexity?

Childhood dream

River Raid, the Atari 8-bit version. My first computer was an Atari back in the 80s, and this particular game occupied a disproportionate amount of my childhood attention.

The ROM is exactly 8kB — almost comical by modern standards. And yet this tiny binary contains everything: graphics, sound, enemy AI, and physics simulation — all compressed into hand-optimized 6502 assembly.

The objective was straightforward: unlimited lives. It’s the quintessential hack, a rite of passage that kids with hex editors performed for entertainment back in the 80s. In 2025, instead of a hex editor, I have an AI.

Setup

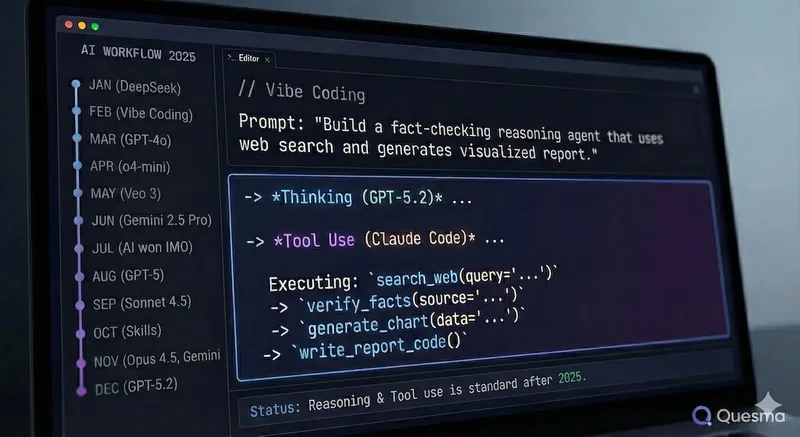

Ghidra doesn’t have a native AI assistant, so I needed a way to bridge the gap between my instructions and the tool’s internal API. This is where the Model Context Protocol (MCP) comes in.

I found an open-source MCP server for Ghidra — essentially a connector that allows Claude to talk directly to Ghidra. The concept is elegant: Claude connects to the running Ghidra instance, analyzes the binary, renames functions, and identifies code patterns programmatically.

In practice, the experience was considerably less elegant:

- MCP has no standard distribution format (e.g., Docker, npm) — you git clone and hope for the best.

- The resulting chain is: Claude → MCP server → Ghidra extension → Ghidra. Four components, four places where things can break.

AI meets 6502

Here’s the thing: I don’t use disassemblers daily. Ghidra’s workflow was completely foreign to me. The whole point was to see if AI could bridge that gap — I’d feed it a mysterious binary, and the Ghidra + LLM combination would figure out it’s a cartridge dump, handle the memory mapping, and guide me through.

Reality was harsher. To test the AI properly, I renamed the binary to a.rom — no helpful filename hints. When importing, I selected only the CPU architecture (6502) without specifying the platform. Claude’s first instinct was reasonable: it asked for the MD5 hash to search for known ROM signatures. The MCP tools don’t expose hashing, so that avenue closed immediately.

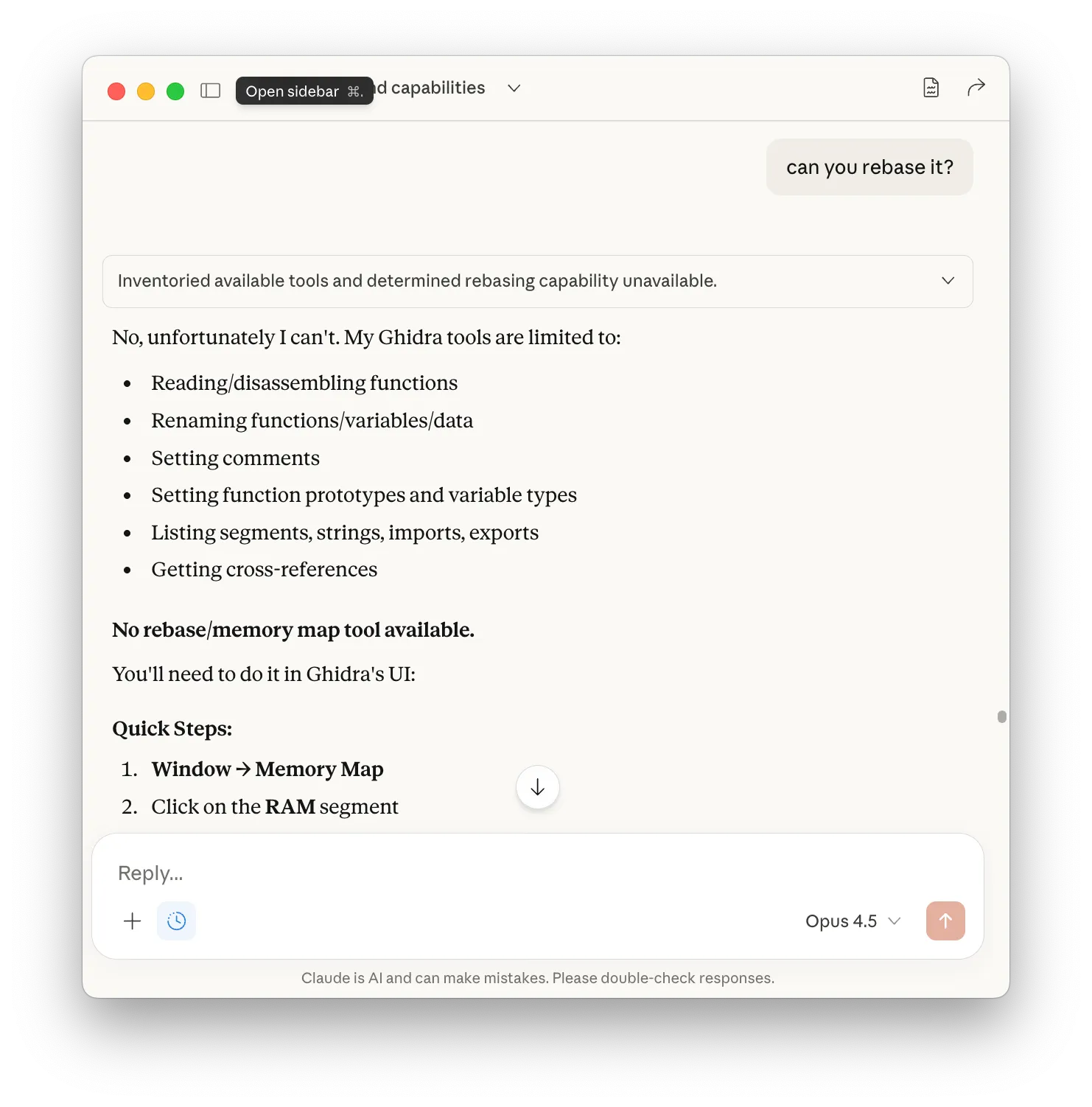

First problem: Ghidra loaded the ROM at $0000, not $A000 where Atari cartridges live. All cross-references pointed nowhere.

Claude identified the issue with admirable clarity: “The ROM should be loaded at $A000, not $0000. You’ll need to rebase the memory image.”

Me: “Can you perform the rebase?”

Claude: “Unfortunately, no. The MCP tools don’t have write access for that particular operation.”

I rebased manually to $8000 — still wrong. The code referenced $A000-$BFFF. Rebased again.

Two rebasing operations in total, neither of which the AI could perform.

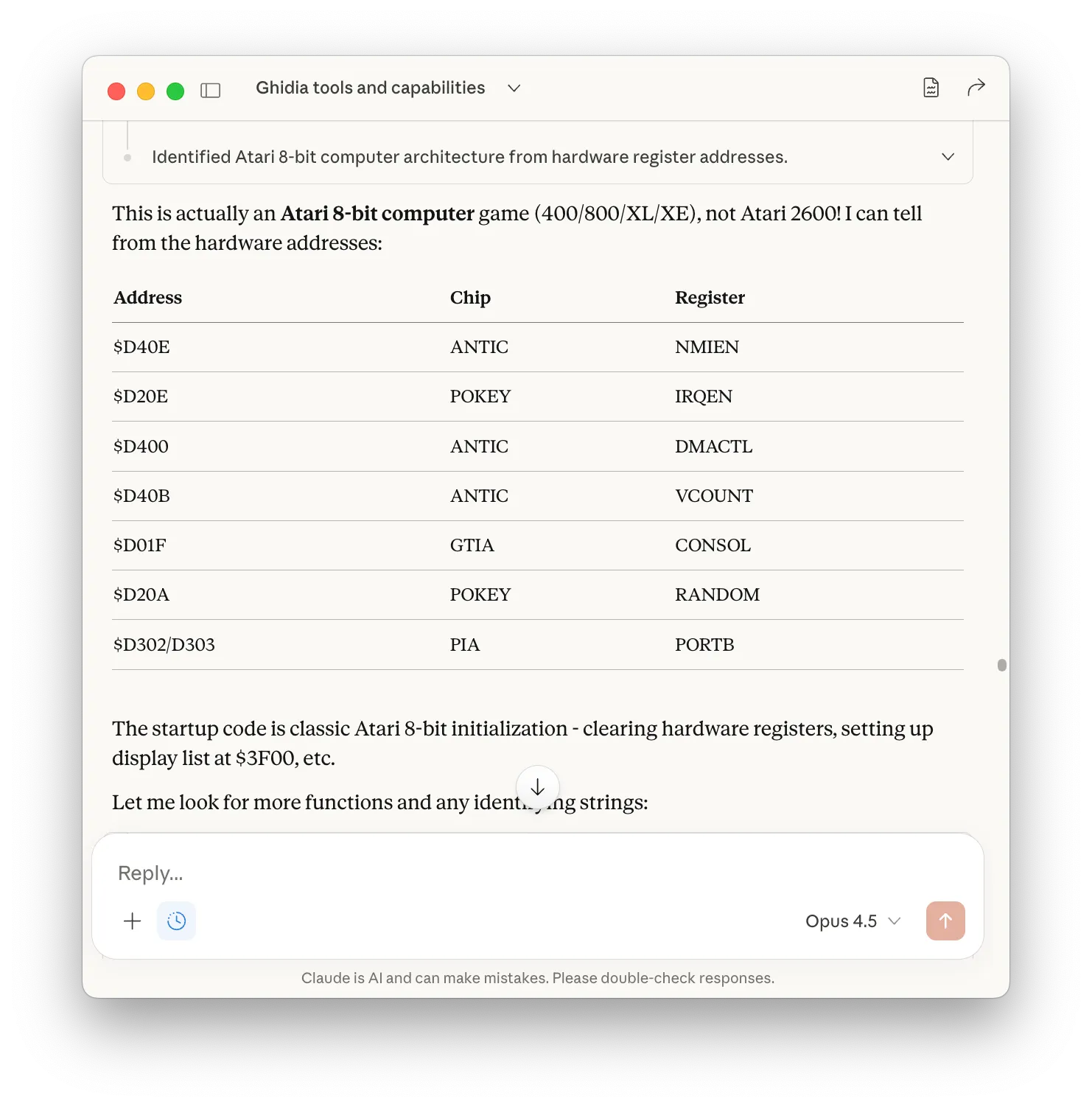

Where Claude genuinely excelled was in identifying the target platform through hardware register analysis:

Hardware addresses are essentially fingerprints that can’t be faked, and these particular addresses are unmistakably Atari 8-bit.

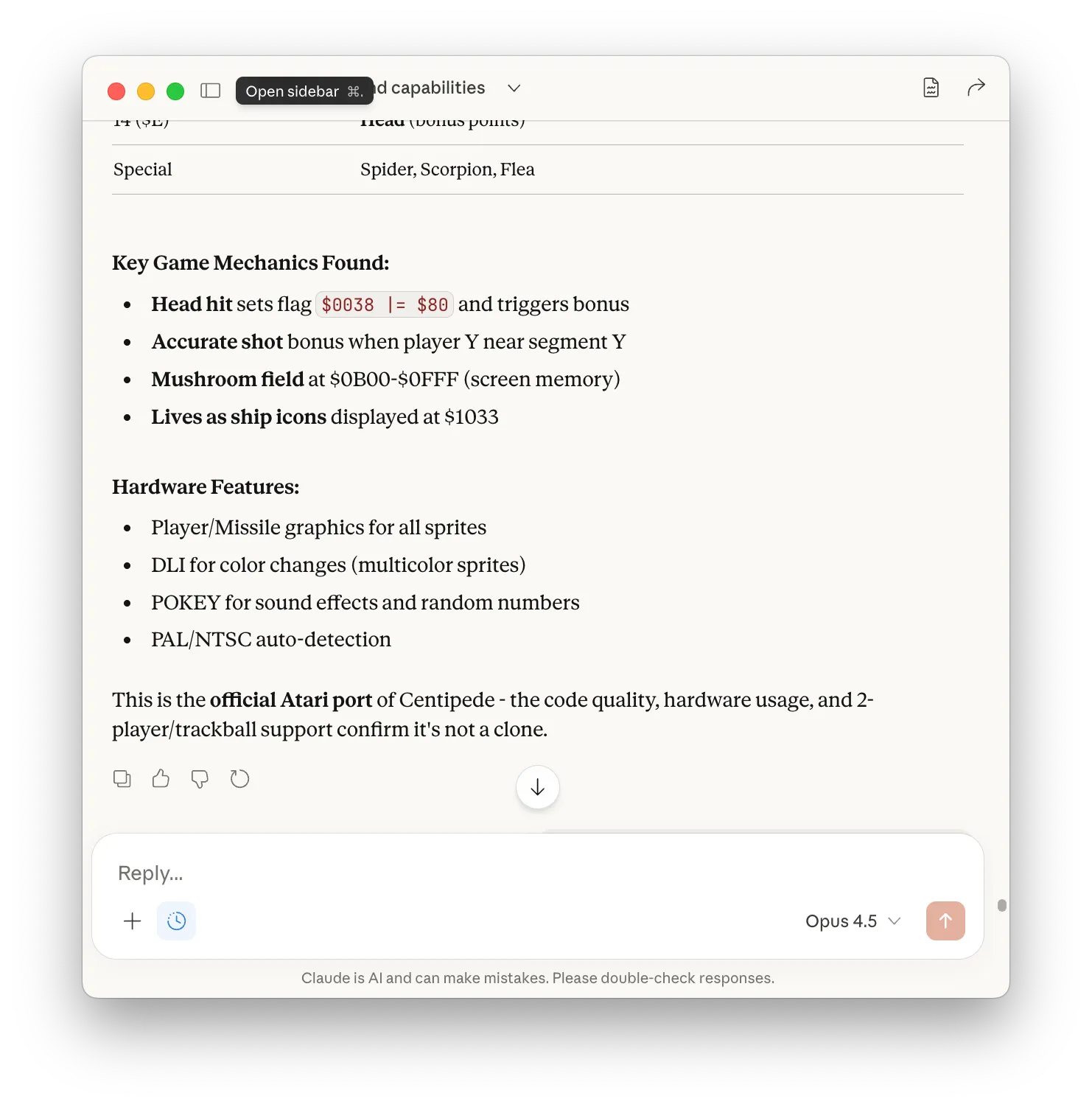

I asked Claude to attempt identification of the game based purely on code patterns and structural analysis. It examined the evidence methodically. Based on this evidence, Claude reached its conclusion:

It was, of course, not Centipede. It was River Raid.

This serves as a useful reminder that confidence and accuracy are orthogonal properties.

The hack

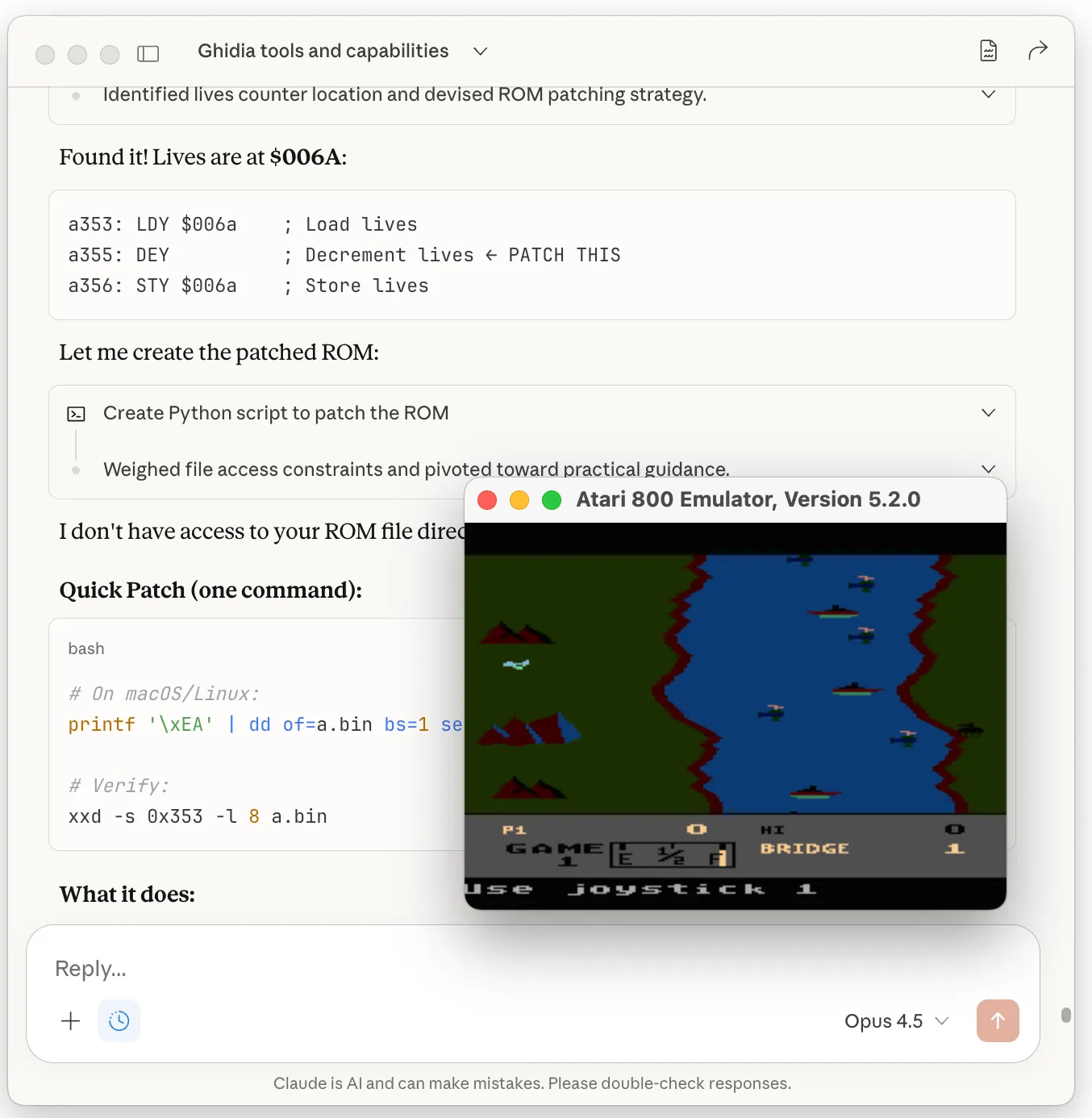

Despite the identity crisis, Claude still understood the code structure. Finding the lives decrement was straightforward. Claude searched for the canonical pattern: load, decrement, store.

The fix is elegantly simple: replace DEY (decrement Y register) with NOP (no operation). A single byte modification, where $88 becomes $EA.

Since the MCP tool couldn’t write the binary directly, I applied the patch externally:

printf '\xEA' | dd of=riverraid.bin bs=1 seek=$((0x355)) conv=notruncI tested the patched ROM in an emulator by deliberately crashing into a bridge. The lives counter remained stubbornly fixed at 3.

The hack works as intended.

What worked, what didn’t

Claude excelled at pattern recognition — hardware registers, code flow, finding the patch location. It struggled with tasks requiring broader context, such as identifying the game or analyzing sprite data.

Setting up MCP is a troubleshooting ritual. It eventually worked, but the experience was painfully slow. Claude would fire off a batch of tool calls, some taking 30 seconds each. Too slow for an interactive session — I’d rather have quick responses with clarifying questions than watch a progress bar crawl. We need a better balance between autonomous batch processing and interactive guidance.

AI should be embedded in every complex GUI tool. We’re in the experimental phase now. Some things work, some don’t. Ideally AI should smooth out the experience in ways traditional help systems never could — compacted Stack Overflow knowledge, real context-aware assistance, and the ability to actually perform tasks rather than just describe them.

Stay tuned for future posts and releases