A postmortem on our $2.5M database gateway: lessons from pilot purgatory

We had all the right ingredients for a successful startup: a clear value proposition, strong problem validation that attracted VCs, high-profile pilots, and a great team. But it wasn’t enough. A year after raising $2.5M, we sold our tech for parts and pivoted.

This is the story of what went wrong, and what I learned.

Failure is a cursed word. Yet, 95% of startups fail, but we usually hear the success stories. This is my attempt to fill that gap.

Survivorship bias as covered by xkcd - we only hear about the winners.

From an IPO to a new venture

I worked 10 years at Sumo Logic - from its early stage of 20-ish people team in Redwood City, from its IPO - and leading a team of over 70 people in Warsaw. Then, hungry for new project, I spent 9 months exploring startup ideas. After 80+ customer discovery calls, I found a pattern: database changes are hard, and a proxy layer could help. Many proxies already exist, though they target a narrow use case (e.g. PgBouncer) while we could capture a wider use case.

The equal co-founder trap

I was obsessed with having an equal co-founder – smart people said it was a must-have. Paul Graham listed “a single founder” as the number one reason why startups fail. I spent months on that, eventually convincing my former partner from Sumo Logic to join my venture.

In retrospect, this was my biggest mistake. I convinced a friend to be an entrepreneur – someone who is successful at established companies but didn’t have the zero-to-one entrepreneurship gene. And it backfired. Startups are not a smaller version of big companies. We ended up splitting after a year.

I paid the price twice - months recruiting my co-founder, then even more time splitting up. We got a clean cap table, but I could have moved faster alone.

I believe the stigma against single founders is outdated and wrong. Instead, we should embrace more models. I was able to find excellent founding employees with great ownership. A good paycheck is one thing. But without a co-founder, I could additionally offer more equity. It attracts great engineers who love early-stage vibes and want to co-own the success.

Lesson #1: A strong founding team with significant equity is more valuable than forcing an equal co-founder relationship.

The honeymoon: $2.5M and a two-pizza team

Raising our initial $2.5M proved to be more than doable. My Sumo Logic experience paid off twofold - for being an early employee of a billion-dollar outcome helped get initial attention, and via angel investment of my former boss. We had a contrarian market thesis “legacy database modernization is a massive opportunity” in a big market with many prospects validating the need for our product. Having prospects willing to speak with VCs helped too. Organizing a two-week roadshow with 50+ VCs was intense but incredibly fun.

Recruiting the initial founding team of six people and setting up the company (from legal through lead generation to office lease) took two months. We started with my co-founder working daily in September, and by the Christmas Party, we had a team and money in the bank. We rebranded from RefactorDB to Quesma - from QUEry SMart. We also narrowed our focus to deliver an MVP: a proxy translating ElasticSearch queries to ClickHouse SQL.

Lesson #2: A two-pizza team is an excellent size for the pre-product market fit stage.

Words vs. actions: When validation isn’t enough

Our customer development focused on finding more potential customers, though a challenging trend appeared. We found big companies with strong problem validation. They accepted our solution, but we weren’t sure how to turn their interest into a real commitment without a product.

Lesson #3: Require a concrete action from the customer (like running a script) to validate their intent.

Database proxies are hard – Vitess took eight years at Google before PlanetScale monetized it. I was delusional about timelines. Our ElasticSearch-to-ClickHouse MVP took 9 months instead of 5. Early pilots uncovered flaws we fixed through Herculean effort (the pancake project was my favorite).

Moreover, our initial market proved to be way more niche. Though ELK stack (Elasticsearch, Kibana and Logstash) showed up in a lot of LinkedIn resumes, many of those companies had migrated to a different stack or planned to. The best early adopters were already gone – they had migrated on their own before we launched. Instead, we targeted mostly big established companies that need more validation (late majority or laggards by Crossing the Chasm definition).

Lesson #4: Cost savings need to make an impact at the top-line; generating new revenue is a much easier sell.

Forever in pilot purgatory

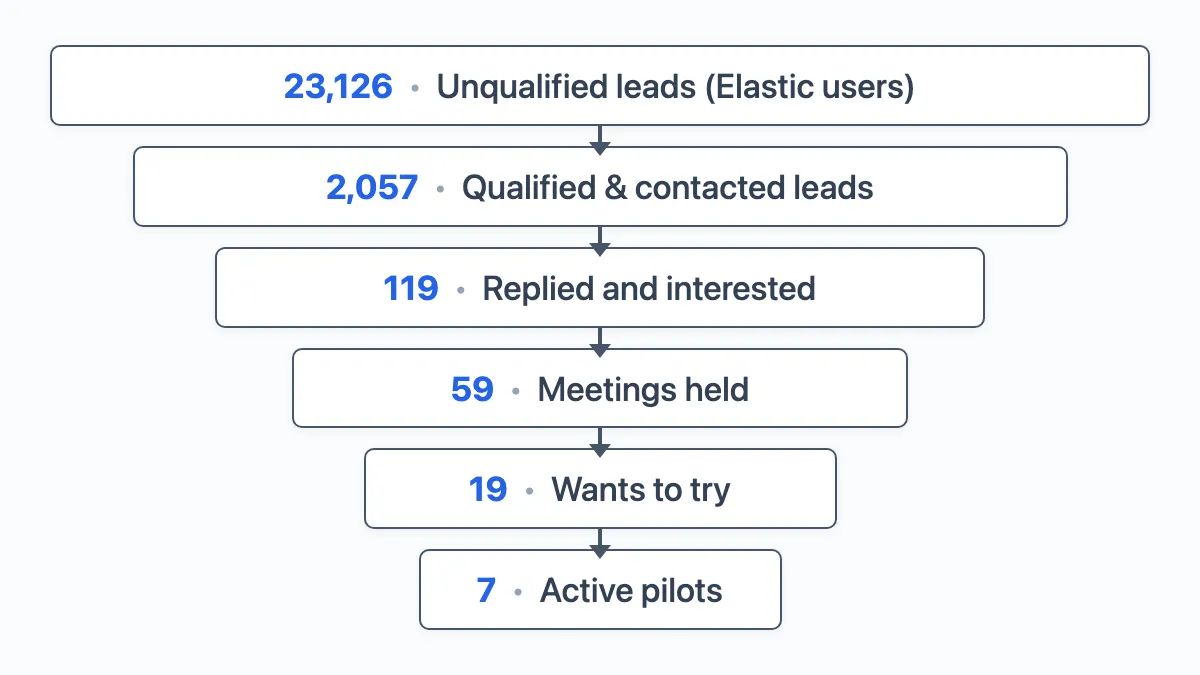

In Summer 2024 we were sending out an early adopter version. We noticed a huge drop from verbally interested people to those who actually tried running it. Even though though the profile was high, including a Fortune 500 company (a few established billion-dollar companies as well as a major telco), the volume was low. I hoped we’d speed up once we launched.

In August 2024 we landed our first major client with a simple painkiller solution. Their data platform got new prospects who demanded Kibana compatibility. We were their only option for that.

In October 2024 we launched around the time of KubeCon conference.

Lesson #5: Skip conferences booths pre-PMF; they’re too slow and too broad to drive meaningful learnings.

Splitting with the co-founder

Meanwhile, our co-founder relationship deteriorated. We disagreed on fundamental decisions. Some disagreements with my co-founder started to show up. I wanted to do more outbound and he preferred focusing on conference booths. I was pushing him to be more hands-on and show more initiative, while he perceived me as aggressive and chaotic. We avoided conflict, leaving our differences unresolved. We should have had a hard conversation around that time. A combination of travel, hard work, hectic high-profile pilot (in an air-gapped environment), and personal issues wore me out too. The traction was not hitting our goals. A lot of promising signs, but forever in the pilot waiting game.

After many hard conversations, we agreed to split up on reasonable terms. We announced the split on the first work day of January 2025.

Are we a feature or a product?

Remaining a lonely founder was hard, but the team stayed strong and nobody else left. However, our biggest potential deal (six-figure ARR) went south. I pushed hard and generated more leads, but discovered a similar trajectory. After analyzing lost deals, we reached the same conclusion. We were never their top 5 priority. Usually we ranked around 12th priority at companies that only complete their top 2-3 items each quarter. We badly lacked urgency. If you’ve tolerated legacy software for years, why act now?

Around 20 companies use us regularly, mostly for free, and growing slowly. A few database companies want to partner, but it means more work for us. The biggest challenge was that we wanted to be independent, but end users just wanted us to fill the gap in their existing data solution. Moreover, AI coding assistants are making database migrations faster and cheaper, undermining the assumption that migration complexity creates sustained demand for database proxy solutions.

At the same time, our biggest customer, Hydrolix, grew 8x in 2024 and raised $80M in Series C.

Lesson #6: Are you a feature or a product? Could you evolve from feature to product?

I told the board that we should pivot. My VCs, Tomasz Swieboda from Inovo and Christian Jepsen from Heartcore, were extremely helpful. Luckily, our technology helped database companies close new deals. It neutralized a key objection, enabling some deals.

The good failure: Selling and pivoting

We ended up selling our IP as an asset sale to Hydrolix. I’m grateful to Marty Kagan, Hydrolix’s CEO.

This bought us runway for the pivot without bridge funding. And was motivating for the team we delivered a product provides real value - useful and being used.

Many founders would position this as a success story. For me it is mostly a learning experience—a step to create something bigger.

I got some things right and others wrong. That’s the sweet spot of learning - for Reinforcement Learning in AI and for human brains alike.

We are on to the next mission. I love my team, investors, and startup problem-solving. Stay tuned!

Discuss on LinkedIn.

Stay tuned for future posts and releases